ROAD MAP FOR MYANMAR’S SEED SECTOR: 2017-2020

December 2016

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

MINISTRN OF AGRICULTURE, LIVESTOCK & IRRIGATION

THR REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR

Foreword

Seeds are a very important factor for increasing yields and incomes of Myanmar’s farmers. The inherent characteristics of the seed determine to a large extent the production potential and the capacity to withstand diseases and shocks like droughts and floods. Therefore, farmers need access to a diversity of good quality seeds of superior varieties. This enables them to achieve: good and secure yields; adaptation to climatic change; enhanced product quality; export potential; and it thus improves their livelihoods and food security.

This seed sector road map brings together the most important issues in the seed sector of Myanmar, ranging from strengthening the regulatory environment to increasing early generation seed production, and from improving seed marketing to enhancing seed uptake. The Road Map provides practical solutions to several pressing challenges in the seed sector and outlines a number of detailed activities to address them.

The Road Map builds on the existing seed laws, regulations and policies of the Union of Myanmar and its aim is to coordinate and align the upcoming seed projects and initiatives better. As such I expect that the Road Map will be used by the Department of Agriculture and Agricultural Research, the Development Partners and the private sector to jointly enhance the performance of the seed sector.

The Seed Sector Road Map has been extensively discussed during a high-level Seed Seminar at the Park Royal Hotel in Nay Pyi Taw on the 30th of August 2016. The seed seminar was opened by the Myanmar Minister of Agriculture Livestock and Irrigation and brought together representatives from the most important Ministries, the private sector and international organizations. During the seminar a draft Seed Sector Road Map was presented and discussed. After modifications and adjustments were incorporated the Seed Sector Road Map was finalized in November 2016.

It is after these broad consultations and deliberations that the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation fully endorses this Road Map, and it looks forward to the successful implementation of the activities provided in it.

Dr. Ye Tint Tun

Director General

Department of Agriculture

Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation

Introduction

This Road Map has been developed by the Myanmar Agriculture Network, in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, the private seed sector and international development organizations. It was extensively discussed in two rounds of feedback and during the National Seed Workshop on 30 August 2016 in Nay Pyi Taw. The Road Map builds on a number of studies and policy documents that were formulated in the last two years, which were commissioned or supported by organizations like: ADB, FAO, IFPRI, IRRI, MALI, the Netherlands Mission and USAID. The documents describe the wider policy context, strategic directions forward, as well as the practical problems as faced by seed companies and seed growers on the ground.

This Road Map highlights the achievements made so far and the challenges encountered by Myanmar’s seed sector stakeholders. The Road Map looks at both the public sector and private sector and the interaction and collaboration between the two. The main purpose of the Road Map is to come to a joint, strategic agenda for the 2017-2020 period that describes the steps needed to transform the current sector into a vibrant, competitive seed sector, able to cater for the diverse needs of Myanmar’s farmers.

The Road Map is structured as follows: First, the current state of Myanmar’s seed sector is analysed; the current scale of operations, quality and the policy environment. The main opportunities and challenges are derived from this overview. Secondly, a vision with the key objectives of the Road Map is presented; including the focus and scope. After that, the main thrust of the Road Map is highlighted, which is a list of SMART-ly formulated action points. Lastly, the modalities are proposed for guiding the implementation process; the oversightand progress monitoring structures, as well as the facilitation support and its financing.

The Current State of Myanmar’s Seed Sector

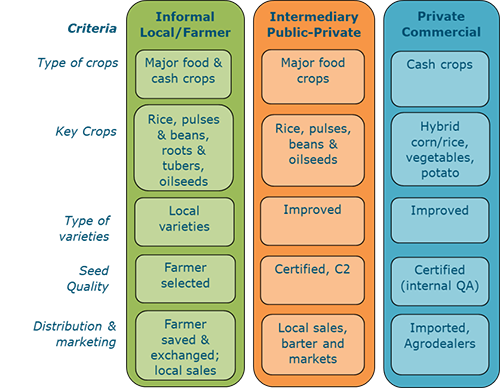

Myanmar’s current seed sector can best be described by three different seed systems:

(1) a system in which farmers reproduce their own seeds of both improved and local varieties (the informal seed system);

(2) a system in which publicly developed, improved varieties are multiplied by individual seed growers and small-scale national seed companies (the intermediary seed system); and

(3) a system in which private companies operate and where privately developed varieties are produced, imported and/or marketed (the formal seed system).

Figure 1:Seed systems in Myanmar and their characteristics

These seed systems operate parallel to each other and mostly cater for different crops and crop value-chains. In the formal system, vegetables and hybrid maize are dominant. The informal and intermediary system largely cater for the other crops like: rice (OP), oilseeds, pulses and beans, and roots and tubers.

Out of the 43 companies active in seed production and distribution, 39 are active in hybrid corn and vegetables. The large majority of these companies are involved in the import and marketing of seeds and agrochemicals with only 7 companies also producing seeds within the country (MALI, 2016). Current estimates are that certified vegetable seeds cover 30-40% of the total vegetable seed market, while hybrid corn seed has a coverage of more than 90% (Htut Oo and Maung Shwe, 2014).

The above indicates that the uptake of certified hybrid corn and vegetable seeds is high, but that the local production of these crops, with exceptions like CP’s production of corn seed, is low. Though 100% ownership is now possible for foreign-owned companies, there are still a number of other factors that limit more commercial seed production in Myanmar:

- Intellectual property rights are not well protected in Myanmar. Companies indicate that strong breeder rights and membership of UPOV would be an advantage for producing in Myanmar.

- The regulations for establishing a seed production company in Myanmar are unclear and cumbersome. Some companies that tried setting up a production company quit in the process due to the long list of requirements and conditions demanded. In addition, varieties of 100% re-exported seed require testing and registration which is not common in other countries in the region.

- It was mentioned that there is a lack of skilled labour; especially for the technical aspects of seed production and quality assurance.

- For exports of seeds some companies indicate that the phytosanitary system has difficulties in providing adequate services for testing for specific organisms and accurately formulating the certificates for different destination countries.

This causes many companies to prefer imports over domestic production; which could be exacerbated when Myanmar fully joins the ASEAN free market.

For the varieties developed in the public sector, the estimate is that farmers buy less than 10% of certified rice seed and less than 1% of certified seed of the other crops – e.g. pulses, beans and oilseeds (Htut Oo and Maung Shwe, 2014; SFSA, 2016). These are rough estimates in which proxies are used for the final seed multiplication stage, which is carried out by individual seed growers (contact farmers or seed village schemes). In recent research it was found that 50% of the seed produced in the public, intermediary system is rejected by the seed testing laboratories (especially for rice), whereas a substantial percentage is not sold as seed but consumed as grain (Subedi et al, 2016). As such, the actual percentages of certified seed sold for rice, legumes and oilseeds are probably much lower than the 10% and 1% indicated above.

Partly as a result of this, the productivity increase in the rice sector has been low. It is estimated that between 2000 and 2011 rice productivity increased marginally, from 3.45 t/ha to 3.66 t/ha; the main production increase, from 21.3 million tons to 32.6 million tons, being attributed to area increase (Htut Oo and Maung Shwe, 2014).

With respect to OP rice, oilseed and legume seeds, a number of reasons are mentioned for the low availability of certified seed. The most important reasons being:

- Limited amount of early generation seed (breeder, foundation and registered seed) produced by the DAR and DOA seed farms due to a lack of resources and staff capacity.

- A system of individual seed growers (contact farmers) that has difficulties in producing sufficient volumes and quality of seed.

- Limited private sector interest to invest in the production of OP rice, oilseed and legume seeds; due to lack of capital, expertise and regulatory challenges.

At the same time, the seed market shows great potential with an estimated value of US$ 480 million (SFSA, 2016) and excellent production conditions, especially in the Dry Zone and Shan State. In addition, current policy changes in terms of 100% ownership for foreign seed companies and a transition towards more liberalized trade agreements with neighbouring countries will create new investment opportunities for the country, both for production and sales.

The Policy Landscape

In the last two years Myanmar has finalized a set of Policies, Laws and Regulations that govern the seed sector. In 2016 alone the Seed Policy, Seed Regulations and the Plant Variety Protection Law were all approved, regulating most aspects of variety registration, seed production and seed business.

Some key characteristics of these laws and regulations are:

- In Myanmar new varieties of all crops require variety registration. For the variety to be released, a trial of at least one season at three locations (in different agro-ecological zones) is needed. The full process to release a variety takes about 10 months from submitting the request at the Ministry to the decision by the National Seed Committee. The associated costs are estimated at MMK 300.000-500.000 per variety (depending on the crop and number of accessions).

- Seed certification (inspection and testing) is compulsory for all seed production intended for domestic market sales. The crops need to be inspected three times on the field and samples need to be sent by the inspectors to the Seed Testing Laboratory. Seeds are checked for: genetic purity, germination rate, physical purity and moisture content.

- Plant Variety Protection (PVP) is being introduced with DUS testing for all registered varieties starting 2016-2017. The duration of the plant breeder’s right is 25 years for new perennial crops and vines, and 20 years for other new plant varieties. The PVP regulations will be developed in 2016 and 2017. The current PVP Law is not in full compliance with UPOV but a process is started to amend the Law to make it UPOV compliant.

Looking at the future, a number of visions and strategies have been developed. Most notably, the 2016 Seed Policy which provides clear policy directions for the future of Myanmar’s seed sector. In addition, the White Paper ‘From Rice Bowl to Food Basket’ (NESAC, 2016) provides strategic guidance for the agriculture sector at large.

Main policy directions have been developed in the National Seed Policy of 2016. The overarching policy direction of the seed policy is to ““gradually reduce the role of the public sector […] to mainly the provision of services and facilitation”. In specific:

- The policy proposes a clearer distinction between public and private activities, whereby the

private sector gradually takes up a greater role in terms of registered and certified seed production, as well as internal quality assurance.

- In the medium term, the policy sees a catalytic role for public seed research,

foundation seed production, the overall seed quality assurance system and seed extension. In

particular the approach of Seed Villages is being highlighted, whereby it is envisaged that organized seed growers at village level produce certified seeds on a commercial basis. In this respect, the policy aims to support the gradual shift from informal to formal seed production for important food security crops.

- To increase the public capacity ensuring timely supply of sufficient breeder and foundation seed and increase the number of seed laboratories, and recruit additional field inspectors to achieve sufficient seed quality control coverage.

Lastly, the policy envisages a more autonomous Seed Certification Unit, a specialized agency that will be responsible for the field inspections, seed testing as well as variety registration (and possible variety protection).

The White Paper, ‘From Rice Bowl to Food Basket’ presents a vision for Myanmar’s agriculture sector. The document formulates the aim for Myanmar’s agriculture sector as “to improve the incomes and livelihoods of rural communities while increasing the availability of more stable, diversified, and nutritious diets to consumers”. The paper focuses on a “demand-led approach driven by domestic consumers and foreign markets with increased productivity throughout the sector”. Furthermore, the document advocates for the breaking down of narrow silos of thinking and communication among the government, private sector and civil society, encouraging more harmonious and coordinated efforts.

With respect to the seed sector the following elements are prioritized:

- “Enact policies to liberalize and invigorate Myanmar’s seed […] markets, while enforcing appropriate quality certification and product safety standards, and encourage the participation of domestic and foreign private-sector firms.

- Continue seed policy reform to permit private sector companies, including multinational companies, to develop and to import and export seeds, subject to appropriate certification.

- With regard to seed, […] government […] staff resources and laboratory facilities are inadequate. Options would be to allow evidence submitted to national seed committees elsewhere in ASEAN be accepted as equivalent to testing in Myanmar, or to outsource certification functions to accredited private seed certification laboratories.”

The policy document clearly emphasizes the need for a good system of quality control and advocates a greater role of the domestic and international private sector to increase the competitiveness of the Myanmar seed sector within the wider ASEAN agricultural economy. As such, the vision document reflects a similar thinking as the Seed Policy, emphasizing a greater role for the private sector; including seed production by groups of farmers and seed companies.

Where can Myanmar be in 5 years from now?

Both in the publicly supported and commercial seed system there is ample scope for improvement. The production conditions for seed are excellent in many parts of the country and there is much knowledge and private interest available to make the sector grow fast. The below vision statements describe where Myanmar can be in 5 years from now, bearing in mind the current state of the sector and policy directions presented above:

Looking 5 years’ ahead, Myanmar can have a vibrant and diverse system of smaller, medium-sized and international seed companies, active in the production and sales of a large diversity of crops and varieties. If a farmer has a need for a new e.g. more disease or drought resistant variety, that demand can be met by the market, and there is a dynamic interaction between the farmers and the seed producers to continuously innovate. The development is supported by a pragmatic and efficient variety release system, and effective system of breeder’s rights.

Looking 5 years’ ahead, Myanmar’s government will be able to adequately monitor the quality of all seed produced and sold in the country. The system ensures that when farmers buy seed it contains what is written on the package (in terms of the variety, the germination percentage and seed health). Also, the producers of seeds are well assisted by an efficient, independent inspection service that allows them to develop their own internal system while gaining the trust from the market. Perpetrators of the law, especially where it concerns those involved in trading counterfeit or illegal seed, are punished adequately.

Looking 5 years’ ahead Myanmar has become an important production centre for hybrid maize and vegetable seed in the world. The global demand for vegetable seeds is increasing rapidly, and Myanmar has excellent production conditions and skilled labour for attracting these type of companies. These companies will be allowed to operate relatively autonomously with their own quality control systems, strong breeder’s rights, while being assisted effectively by the government’s phytosanitary service.

Overall, the next 5 years will require a strong public-private collaboration to ensure the above developments take place. It also requires a clear distinction between the public mandate and private mandate, moving gradually away from a government involved in all aspects of seed production and quality control to the provision of services and facilitation.

…And what does it take to get there…

The Myanmar Seed Sector Road Map 2017-2020

The Road Map is structured along the lines of what is required of the public sector, the private sector and their collaborative activities to achieve the above vision statements. The Action Points are formulated as detailed as possible, indicating the specific activities, timeline and support organizations.

The Public System: Laws, regulations and implementation capacity

The Seed Policy, Seed Law, Plant Variety Protection Law and Seed Regulations have all been approved. Apart from slight modifications and amendments to this legal framework, the emphasis needs to be on its enforcement and building the capacity for the government’s implementation. Concrete actions for strengthening the systems of variety release, variety protection, quality assurance and import/export regulations are:

The Variety Release System

For the VCU testing of varieties clear protocols/guidelines are currently being developed, specifying how new varieties (of e.g. cereals, potatoes, legumes and oilseeds) need to be tested. This includes the selection of trial sites, management practices and evaluation protocols. The further strengthening of these activities will be taken up by the Netherlands ISSD project envisaged for 2017-2020.

A second activity is to explore variety listing (not testing) for all new vegetable varieties (and possibly potatoes). As the turnover and amount of varieties is very high in the vegetable and potato sectors, variety listing could be more appropriate. If varieties have been released successfully abroad, in similar agro-ecological zones, the variety can be approved directly based on the file and with a small registration fee. A similar system is in place in the Philippines and Nepal. The listing can be applied both for the PVR and PVP registration. This policy change needs to be further discussed between MALI and the private sector. The discussion can be facilitated by the IFC-WB project, indicative timeframe for start of activities: Q3-Q4 2017.

The Quality Assurance System

The capacity of the seed inspection and testing staff of MALI requires further strengthening, especially in terms of inspections on genetic purity and testing of seed health. This includes the upgrading of facilities like the seed testing labs, ensuring that at least one laboratory, public or privately run, is ISTA accredited (promoting seed exports). Investments in the physical infrastructure and capacity building can be supported by the KOICA-KSVS project and the MALI/WB ADSP project. These activities are already ongoing but require more collaboration and coordination for the specific elements highlighted above.

At the same time, there is a need to critically look at the development of private sector-led, alternative quality assurance systems. These can include accreditation for well established companies, and quality declared seed and truthfully labelled seed for local seed production. Pilots for these alternative models can be supported by the ISSD project, indicative timeframe for start of activities: Q3-Q4 2017.

The Plant Variety Protection System

As mentioned in the Road Map’s analysis strict enforcement of intellectual property rights are key to attracting foreign companies to invest in seed production in Myanmar. In addition, they can help improved the incentives for domestic breeders both in the public and private sector. Therefore, it is important that Myanmar ensures UPOV membership in the coming years, while in parallel Myanmar develops the capacity for DUS Testing and increasing awareness. In addition, the development of the secondary legislation (regulations and guidelines) will be important to guide the implementation of Breeder Rights. This activity is already being supported by the Netherlands PVP Project, a collaborative effort between MALI and Naktuinbouw in the Netherlands.

Counterfeit and illegal seed

The international seed companies have concerns about the import of illegal or counterfeit seed. This relates to both the import of not registered varieties as well as counterfeit seeds (infringement of trademarks and company brands). In addition, some new varieties are registered under almost similar brand names (e.g. BK-787 instead of BH-787); which should be forbidden in line with international IPR regulations. The Road Map proposes to support the government in better enforcing the existing regulations (e.g. at market outlets) as well as adjusting regulations where necessary to restrict similar naming of variety names. The IFC-WB project will work on this together with MALI. The indicative timeframe for start of this activity is 2017.

Setting up a Production Company

A number of companies complain about the lengthy procedures for setting up a seed production company and the regulatory limitations for operating one. The Road Map proposes to simplify the procedures and reduce the requirements for setting up a company. This mainly concerns the procedures at MALI but also at the MIC. This activity can be supported by the IFC/WB project, focusing on the development of a one-stop shop for seed production company registration, with a clear guideline on the steps to be followed. In addition, existing seed regulations need to be reviewed to include an exception for variety registration for 100% re-exported varieties. The indicative timeframe for start of this activity is Q2-Q3 2017.

Imports and Exports of Seed

A number of importers has reservations about the requirements for importing seeds. The paperwork needed and the process of approval is seen as tedious. This activity needs further follow-up and discussion between MALI and the envisaged National Seed Association of Myanmar (see below).

With respect to exports, the SPS-protocols require special attention. This includes the development of the right phytosanitary protocols for seed, and the ability to provide tailor-made phytosanitary certificates for experts to specific countries (depending on the market conditions).MALI together with an envisaged ADB support activity can further take this up as well as the Dutch support channeled through the NVWA - SPS project envisaged for early 2017.

Cross-cutting: Institutional set up

Taking in mind all of the above, the regulatory environment (for breeder rights, variety release and quality assurance) would benefit from a more autonomous agency. Currently the production of seed at the seed farms, the variety testing and release, and the seed certification service take place by the same department (DOA). Therefore, in line with the approved Seed Policy, a separate, semi-autonomous unit within MALI is proposed, that is responsible for all seed related regulatory issues and their enforcement. This unit should be responsible for all aspects of variety testing and registration (VCU and DUS), seed production inspections, seed laboratory testing and accreditation. Further discussions on the implementation of this policy change can be supported by the ISSD project envisaged for Q1-Q2 2017.

Cross-cutting: The National Seed Reserve

Given the increased volatility in rainfall and related agricultural production, the Seed Policy and SFSA document call for the establishment of a strategic seed reserve, both organized nationally and regionally. The seed reserve should ensure that in times of drought or floods, sufficient seed stock of the best adapted varieties is available for next season’s planting and seed production. The reserve stock should include breeder, foundation, registered, and certified seed of selected crops and varieties. The size of the reserve will be based on the estimated minimum requirement for sustaining the seed industry and meeting the immediate need of certified seeds in case of a calamity.This activity could be taken up by MALI together with an organization like the FAO and/or one of the CGIAR centers (e.g. IRRI and ICRISAT).

The Private System: Seed Production and Sales

Though the above issues also influence the performance of the private sector directly, there are a number of specific issues that hamper the further growth of the commercial seed companies. The main assumption is that there is enough private interest in seed business, but thatthere are too little inspiring business cases existing at the moment. The main topics that need attention are the following:

Skilled Labour

A number of companies indicate that they have difficulties in finding suitable staff, especially in the areas of plant breeding, technical seed production and marketing. Therefore, greater attention needs to be given to specific labor market requirements in the curricula of Yezin Agricultural University and the State Agricultural Institutes. Already a number of activities are in place to further strengthen the capacity of these organizations. In particular the IRRI and ACIAR capacity building and research projects with Yezin Agricultural University and DAR. In addition, the Netherlands will support a number of State Agricultural Institutes in terms of bridging the gap between the competences of the current graduates and labour market demands.

Local Seed Production

The system of seed villages and contact farmers has been well established in Myanmar, but has difficulties in delivering sufficient quality and quantities of seed. The new government has put much emphasis on improving this system, and together with the ‘promotion of quality seed’ the National Seed Sector Workshop ranked this topic highest in importance. The Road Map proposes to develop strong Local Seed Businesses, which can be groups of farmers, larger individual growers or small- and medium sized domestic seed companies. The seed growers can be linked to private seed companies (as outgrowers) or work by themselves. Additional support is required in terms of: training and coaching on technical aspects (variety choice, quality seed production) as well as on seed business management (production planning, forecasting, financial management and marketing). The ISSD project, the SFSA and the ADSP projects will all support a number of activities in this area, focusing on training and coaching of selected groups of seed growers and small-scale seed companies. These activities will start in 2017.

Promotion of Quality Seed

Both for domestic and international companies the promotion of new varieties is important. Currently, the uptake of quality seed of superior varieties is still lagging behind significantly (though growing robustly). The domestic and international seed companies want to further expand their promotion activities, in terms of brochures (good agricultural practices), demonstration fields, seed fairs at township level, and trainings. Also, the government extension system can play an important role in supporting these demonstrations and trainings, as superior seeds have to go hand in hand with better agronomic practices. The promotion of quality seed together with the extension system can be supported by organizations like MEDA and LIFT, as well as the ISSD project.

Infrastructure and Investments

In terms of the production, processing and storage of seed significant investments in infrastructure are required. This especially concerns investment in production technology (mechanization), cleaning, drying and storage facilities. These investments are needed across the board both for domestic and international seed companies. Some form of leverage funding or soft loans need to introduced for this purpose. Projects like LIFT (private sector window), IFC-WBand ADB together with SFSA can play an important role in this.

At the Interface: Public-Private Collaboration &Seed Sector Coordination

One of the main bottlenecks identified is the communication and collaboration within and between the public and the private sector. This is visible in all areas, from limited discussions on new policies, laws and regulations to feedback on the demand forecasting and planning for early generation seed production. This component also includes the role of the government seed farms as they are an important pivot between the public and private sector.

National Seed Association of Myanmar

Next to the smaller seed growers, mainly involved in OP rice, pulses, beans and oilseeds production, Myanmar accommodates more than 40 seed companies. Some of these companies are currently represented through the Fertilizer, Seed and Pesticide Entrepreneurs Association. Given the larger share of fertilizer and pesticide interests in this organization and the specific nature of the seed business, there is an appeal to establish a separate Seed Association of Myanmar. The Association will do the lobby and advocacy for the seed companies on topics mentioned in the regulatory section of the road map and be a sparring partner for the government in policy discussions. In addition, the Association can develop specific services and activities for its members to strengthen their capacity and generate income. Mercy Corps and APSA together with the Netherlands Embassy will provide support for the establishment of a National Seed Association of Myanmar. The finalization of the Constitution and the first General Assembly are envisaged for Q4 of 2016 and Q1 of 2017.

Seed Growers Associations

At different levels of government, the need for regionally organized seed grower associations was advocated. The seed growers’ associations bring together the multitude of individual seed growers; giving a voice to the local seed multipliers of especially rice, oilseeds, pulses and beans. In addition, the associations can jointly estimate their demand for early generation seed and communicate this to the seed farms. The establishment of district and regional seed grower associations will be supported by the ISSD project. This activity is initially envisaged for a pilot with a number of selected districts in four regions in the period 2017-2018. If successful upscaling can take place between 2019 and 2020.

Licensing of public varieties

To encourage uptake of new varieties, a system of (exclusive) licensing of public varieties can be introduced. Already a number of CGIAR and National Agricultural Research centres are experimenting with this, with some success. A pilot could include the licensing of public-bred varieties to local private seed companies. Some form of exclusivity could protect the company from competition for the first years facilitating the building of a brand and reputation. The ISSD project and/or the envisaged ADB SFSA project can pilot a number of (exclusive) licensing agreements between DAR and a local private company, as well as develop the necessary guidelines and procedures.

The Seed Farms and Early Generation Seed Production

With respect to the system of research and early generation seed production, the prime focus should be on supporting the emerging private sector with new varieties and good quality foundation (and registered) seed. A specific distinction needs to be made between the DAR seed farms focusing on varietal development, agronomic research and promoting the uptake of varieties; and the DOA seed farms aggressively working on multiplying the varieties into sufficient quantities of foundation (and registered) seed. In all cases, hybrid seed production (including of rice and sunflower) can best be left to the private sector, whereas the public sector focuses on open pollinating crops and varieties of food crops like rice, legumes and oilseeds.

The mandate and focus of the seed farms is crucial in this, requiring a shift towards a combination of more autonomy with greater accountability. Specific public-private business models have been developed in other countries which could be introduced to Myanmar as well. Models successfully implemented in other countries include the outsourcing of early generation seed production through contract farming; performance contracts of seed farms and the introduction of internally generated funds. It is important that reforms and investments go hand in hand – providing the right incentives for seed farm staff and management. In addition, close collaboration with the private sector (seed companies and seed growers) is required to plan for adequate supply of the right crops and varieties. The infrastructure investments can be supported in the Dry Zone for at least 10 DOA and DAR seed farms through the ADSP project. In addition, the ISSD project will support a number of seed farms in piloting new institutional arrangements.

Seed Sector Coordination Platform

In order to stimulate dialogue between the public and private sector and to undertake seed chain planning for the upcoming seasons, biannual National Seed Sector Platform meetings are proposed that bring together key representatives from the public sector, private sector and international organizations. The seed platforms will discuss the regulatory environment, undertake seed demand forecasting and plan for EGS requirements of specific crops and varieties. The IFC-WB project will support these platforms, while the organization will be jointly taken up by MALI and the envisaged National Seed Association of Myanmar. A first platform meeting is envisaged for Q4 2016.

ACTION AGENDA – SEED SECTOR DEVELOPMENT IN MYANMAR

14 JUNE, 2017

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE LIVESTOCK & IRRIGATION

Foreword

After the approval of the National Seed Sector Road Map in December 2016, the Ministry of Agriculture Livestock and Irrigation has deemed it important to further operationalize the policy ambitions as expressed in that document. This has led to the preparation of an Action Agenda. The Action Agenda brings together the most important activities that need to takes place in the next two to three years in order to achieve a vibrant an competitive seed sector in Myanmar. A seed sector that is able to cater for the diverse needs of Myanmar's farmers.

The Action Agenda builds on the Seed Sector Road Map of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar and its ami to align all government and project activities better, ensuring complementarity between development projects and organizing a joint learning platform. As such I expect that the Action Agenda will be used by the Department of Argiculture (DOA) and Department of Agricultural Research (DAR), the private seed sector and the Development Partners jointly to enhance the performance of the seed sector.

The Action Agenda is organized around the eight most pressing topics in the seed sector, ranging from increasing local seed productin and marketing, to developing and effective and decentralized seed quality assurance systems; The action agenda is very sepcific and highlights 23 activities with a description of: the challenges at hand, the envisaged activities as well as timeline with designated tasks per stakeholder. The activities were intensively discussed during the first Seed Sector Platform meeting in Nay Pyi Taw, on the 4th of April 2017, in which the participants presented their views on the required changes.

Over the next years we will monitor the projress of the implementation of the Road Map through biannual National Seed Sector Platform meetings, coordianted by the MOALI. At these meetings we will ensure that an adequate mix of seed sector stakeholders if present, including representatives from the private sector, inernational organizations and NGOs active in the seed sector.

It is after broad consultations and deliberations that the Miistry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation fully approves this Action Agenda, and it looks forword to the successful implementation of the activities provided in it.

DR. Ye Tint Tun

Director Grneral

Department of Agriculture

Union Ministry of Agriculture Livestock and Irrigation

Introduction: National Seed Sector Platform Meeting

The Action Agenda has been developed during a large public-private gathering in Nay Pyi Taw, on 4 April 2017. At the meeting there was high-level representation of the government, the private sector and development partners. The organizations present included: the Department of Agriculture, Department of Agriculture Research, Department of Agricultural Planning, the National Seed Association of Myanmar (NSAM), the Myanmar Agriculture Network (MAN), the International Finance Corporation of the World Bank (IFC-WB), Livelihoods and Food Security Trust Fund (LIFT), Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) and the Agriculture Development Support Project (MOALI/WB ADSP). Together the participants agreed that greater coordination and alignment is necessary between government and support activities. The Action Agenda aims to divide tasks between support projects and presents a coordination structure for subsequent platform meetings and monitoring of progress.

The Action Agenda builds on the Seed Sector Road Map that was approved in December 2016. The Road Map brings together the main policy ambitions of the government in terms of: (1) the enabling environment (including company legislation, plant variety release, quality assurance, plant breeder’s rights and imports and exports); (2) public sector development (related to breeding, early generation seed, seed testing and inspections); (3) private sector development (focusing at infrastructure development, capacity development and support for local seed production); and (4) seed sector coordination (with respect to the establishment of a national seed association, regional seed growers association and the seed sector coordination platform). The full Seed Sector Road Map is available with the MOALI Seed Division, and can be provided on request.

During the National Seed Sector Platform the Director General of Agriculture, Dr. Ye Tint Tun indicated that the private sector should lead the seed sector, and that in the field of quality assurance trusted companies can play an important role. The government is ready to support private seed testing laboratories, and the Seed Law allows for this. Also, in terms of early generation seed production (including breeder seed, foundation seed and registered seed) the private sector is encouraged to play a more active part.

Coinciding with the first National Seed Sector Platform was the Launch of the Integrated Seed Sector Development (ISSD) Myanmar Programme by the Myanmar Union Minister of Agriculture and Netherlands Embassy. The ISSD Myanmar Programme will initially facilitate the Seed Sector Platform Meetings and will, together with a large number of development partners, support the implementation of the Action Agenda.

Signing ceremony for the ISSD Myanmar programme, between DG DOA, Dr. Ye Tint Tun and the Netherlands Ambassador to Myanmar, Mr. Wouter Jurgens

The Action Agenda

Action Agenda 1: Local seed production & marketing

The Road Map proposes to expand local seed production, especially for crops like rice, oilseeds, and pulses and beans. This is envisaged through the organization of groups of farmers; enhancing the capacity of larger individual seed growers and small- and medium-sized domestic seed companies. The group discussed how to further operationalize this and come up with concrete activities and responsibles.

| Challenge | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

Insufficient volumes of quality |

Pilot a number of seed |

MOALI-DOA, ISSD Myanmar and MOALI: Public-Private Dialogue on the |

| The lack of a viable seed business model for local seed production was identified as the major constraint for boosting local seed production and sales. Existing contact farmers are operating at a very small scale and are scattered around the country. At the moment the Township office has difficulties providing all necessary support. The solution is to link well-performing seed producers to private seed companies. A precondition for sharply increasing local seed production, is that DOA and DAR stop certified seed production and stimulate private seed companies to take up that role. Apart from ISSD Myanmar other projects can support this agenda as well, like LIFT and ADSP. | ||

| Challenge | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

Limited quality assurance (QA) |

Development of an alternative |

MOALI-Seed Division together with |

| There is limited staff and inadequate capacity available at the seed testing laboratories, both in terms of human resources and physical infrastructure. At the same time the demand for QA services is increasing. Alongside the regular certification system an alternative system will be developed: either Quality Declared Seed (QDS) or Truthfully Labelled Seed (TLS). This will be done in close collaboration between the government and the regional seed growers association, with support from IFC Myanmar. | ||

| Challenge | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

Scientific evidence on |

Proving the business case and |

Seed farm or seed company together |

| The business case on quality seed will create clarity on the added value of using certified seed of an improved variety compared to farm saved seed of a local variety. Undertaking this economic analysis and sharing it within the research and extension system, as well as with the private sector, can significantly increase seed production and marketing | ||

Action Agenda 2: Stimulating private investment in the seed sector

The Road Map covers a number of issues with respect to private sector investment. These include the enhancement of the capacity on seed production and quality assurance. The Road Map proposes greater attention for the inclusion of specific labor market requirements in the curricula of Yezin Agricultural University and the State Agricultural Institutes. In addition, investments need to be made in the infrastructure of seed companies in production technology (mechanization), cleaning, drying and storage. These investments are needed across the board; both for domestic and international seed companies.

| Challenge | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

There are a number of |

The laws, regulations and |

MOALI with support of IFC and NSAM |

| The biggest issue at the moment is of phytosanitary nature. This includes the Pest Risk Analysis requirement. But also for exports (e.g. of rice) clearer regulations are required. In addition to these specific seed related regulations, other general investment related issues are an obstacle for investments in seed production; these include: obtaining land and permits for construction. Better collaboration between government agencies (e.g. MOALI and MIC) is required here. | ||

| Challenge | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

Illegal imports of seed: no |

Need to develop action plan to |

MOALI with support of IFC and NSAM |

| By the private sector this is seen as one of the biggest problems at the moment. It is estimated that Shan State alone imports 2.000 tons of hybrid maize seed illegally per year. The problem goes beyond seeds, and is experienced by the entire agro-input sector (including pesticides and fertilizers); a concerted effort is required. | ||

| Challenge | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

For producing seed within |

Incentive package for domestic |

MOALI, IFC, JICA, UNOPS-LIFT; specific |

| These aspects affect the overall competitiveness of seed production in Myanmar. Especially the land issues were emphasized. Not only the land as such, but also the designated function of the land. Some companies pulled out of seed production because it was easier and cheaper to produce in neighbouring Thailand. With the above package of land, finance and tax incentives this can be overturned. | ||

Topic 5: Early generation seed matching supply and demand

The supply of early generation seed (breeder, foundation and registered seed) is not able to fully meet the demand of customers (especially for non-rice crops). There is a significant gap for registered seed of in-demand varieties. Further, there are only a few private seed companies that are involved in the production of certified seed of pulses and oilseed crops. Key action points are:

| Challenge | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

Lack of EGS seed demand |

Piloting seed demand forecast |

MSU, IFPRI and ISSD in collaboration |

| Currently, the breeder (BS) and foundation seed (FS) production planning is organised 6 months in advance. However, the demand for registered seed (RS) is organised on a very short or ad-hoc basis. This is also a reason behind the supply gap of RS. Therefore, the Action Agenda aims to conduct studies for the EGS demand in selected regions of the Dry Zone. The studies will inform the MOALI (DOA and DAR) seed farms for their multi-annual production planning. | ||

| Challenge | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

Inadequate funding available |

Implementing the guide line that |

MOALI (DOA and DAR) with support |

| The Platform proposed that the seed farm’s efficiency in EGS production can be greatly enhanced if there is a system that allows for retention of funds as a percentage of the seed farms’ revenue. This is a fundamental change in the financing of the seed farms, and will require guidelines which describe the rules/procedures for using the funds; ensuring accountability and transparency. | ||

| Challenge | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

Lack of participation of private seed |

Develop an information system |

DAR, DOA, MOC; this is part of the EGS |

| Private seed companies’ involvement in seed production of pulses and oilseeds is almost non-existent in Myanmar. However, private seed companies are interested if they have access to information on variety suitability, marketability and export potential. On the other hand, it is also suggested that the production of RS (currently the responsibility of DOA) should be organised with private seed companies (possibly including licensing of public varieties). This can encourage private seed companies to get more involved in pulses and oilseeds production. | ||

Action Agenda 6: Promoting uptake of quality seed

Both for domestic and international companies the promotion of new varieties is important. Currently, the uptake of quality seed of superior varieties is still lagging behind significantly (though growing robustly). The domestic and international seed companies want to further expand their promotion activities, in terms of brochures (good agricultural practices), demonstration fields, seed fairs at township level, and trainings. Also, the government extension system can play a role in supporting private demonstrations and trainings, as superior seeds have to go hand in hand with better agronomic practices.

| Challenge | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

Public research and extension |

Research will focus more on |

DAR and DOA Extension, |

| There needs to be more attention for the adoption of new varieties. Demonstrations and trainings can help in convincing farmers of the superiority of new varieties. Research (DAR) and extension (DOA) will need to play a greater role in this. | ||

| Challenge | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

There is competition between |

DOA and DAR should leave |

Start a pilot between DAR and a |

| Hybrids in many countries are left to the private sector, because of the commercial value and more efficient production systems. Much effort has been put in the research of public hybrids and in order to valorise this a licensing agreement (with a fee or royalty) can be discussed between DAR and a private company. | ||

| Challenge | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

Package sizes are often too big |

Work on smaller package sizes |

Start working on this with |

| For a farmer to try out a new variety 25 kg bags (e.g. for 2 acres) are too big. Often farmers want to try out small quantities first before converting to their entire farm. Small packs (of e.g. 2 kg or 5 kg for rice) can be a good solution for this. | ||

Topic 7: Effective and decentralised seed quality assurance systems

At the moment the formal government supported seed quality assurance system has difficulties reaching all seed producers, both geographically as well as at the different stages of seed production. Already many investments have been made in the upgrading of the public seed laboratories (especially in Yangon, Nay Pyi Taw and Mandalay). Especially the new seed testing laboratory in Nay Pyi Taw could serve as a reference laboratory for Myanmar. At the same time, internal seed quality assurance systems by private seed companies with accreditation through DOA could fill a significant gap in seed quality assurance services. Further, post-control tests can provide additional checks for the seeds that currently are available in the market.

| Challenge | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

Insufficient seed quality |

Develop a system of |

DOA to develop a directive and |

| The current seed quality assurance system is not able to fully meet the services for all seed producers and companies in the country. The seed law and the seed regulation allow the private sector to set up their own seed testing laboratory (and related internal seed quality assurance system). This opening in the law needs further operationalization for which support from IFC and input from NSAM is required. This activity can be linked to the development of truthfully labelled seed (TLS) from action Agenda point 1 (Local seed production and marketing) where this activity is proposed. | ||

| Challenge | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

Lack of a system of post-control |

Develop guidelines for a |

DOA will develop this system |

| Frequently farmers are complaining about the low quality of certified seed. There are stories of entire containers of seed that had low levels of germination, because of long distance transport. Other reasons for lower than labelled quality can be poor storage at the agrodealer ship, seed mixtures at point of sales or bad handling during transport and (un)loading. The Platform recommends that (risk based) post control checks at import/wholesale level and at the point of sales (e.g. agro-dealers shops) are needed to prevent bad quality seed reaching the farmer. This in turn first requires the development of guidelines on postcontrol checks and inclusion in the seed regulations. | ||

Action Agenda 8: Operational Guidelines for the Seed Sector Platform

The Road Map agreed on the organization of biannual National Seed Sector Platform meetings, bringing together key representatives from the public sector, private sector and international organizations. The objective of the Platform is to stimulate dialogue between the public and the private sector and to undertake seed chain planning. The seed platform will discuss on the regulatory environment, undertake seed demand forecasting and plan for EGS requirements of specific crops and varieties.

| Issue | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

It is important to have full |

DOA will make a list of 60 |

MOALI-DOA, NSAM and ISSD Myanmar |

| In order to ensure continuity in the activities of the Seed Sector Platform meetings it is important to have continuity in the participants that attend the meeting. The list is also used to provide regular updates and invite people for other seed related events. The Platform’s Secretariat (see below) is requested to develop this list and request organizations to nominate candidates for the Platform Meetings. | ||

| Issue | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

There needs to be follow-up in |

A Platform Secretariat will be |

2 DOA, 1 DAR, 2 NSAM, 1 Regional |

| It was decided to establish a secretariat that monitors the implementation of the road map and prepares the biannual platform meetings. The secretariat represents all parts of the seed value-chain, from breeding, EGS and research (DAR and ACIAR), to regulations and enforcement (DOA and IFC), to seed production and business (NSAM, RSGA and ISSD). People are nominated by their respective organizations. | ||

| Issue | Action agenda | Roles and timeline |

|

We need to have a balanced |

For the next Platform Meeting: |

(1) DAR; (2) DOA; (3) APSA/NSAM; |

| It was decided to establish a small secretariat that monitors the implementation of the road map and prepares the Platform meetings. The secretariat represents key parts of the seed value-chain, from breeding, EGS production and research (DAR and ACIAR), to the regulations and their implementation (DOA and IFC), to certified seed production and seed business (NSAM, RSGA and ISSD). The specific people will be nominated by the respective organizations. | ||

For More Information: